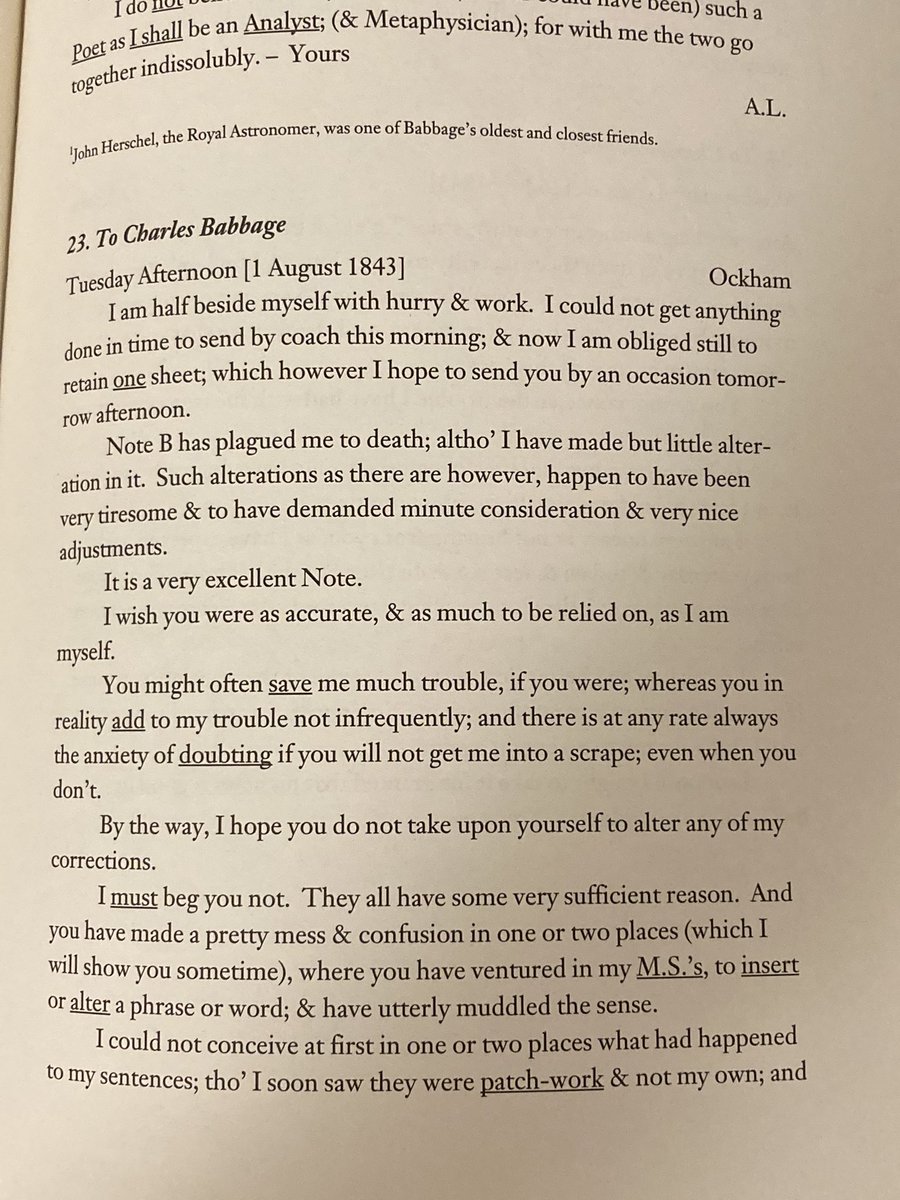

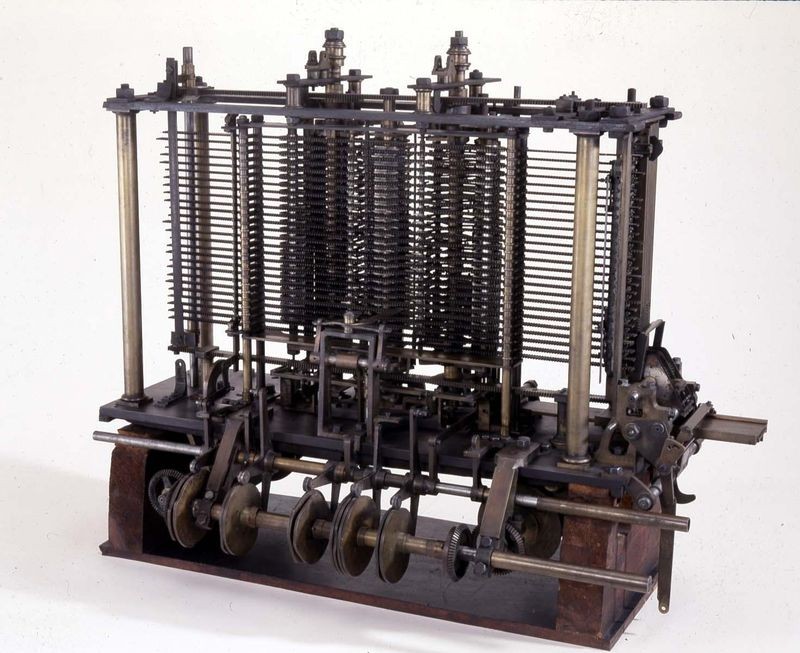

Lovelace had to sign her work with just her initials because women weren’t thought of as proper authors at the time. Though never formally trained as a mathematician, Lovelace was able to see beyond the limitations of Babbage’s invention and imagine the power and potential of programmable computers also, she was a woman, and women in the first half of the 19th century were typically not seen as suited for this type of career. Her notes, which included a method for calculating the Bernoulli numbers sequence and for what would become known as the “Lovelace objection,” were the first computer programs on record, even though the machine could not actually be built at the time. Although originally retained solely to translate the article, Lovelace also scribbled extensive ideas about the machine into the margins, adding her unique insight, seeing that the Analytical Engine could be used to decode symbols and to make music, art, and graphics.

(She was also the daughter of the poet Lord Byron, who invited Mary Shelley to his house in Geneva for a weekend of merriment and a challenge to write a ghost story, which would become Frankenstein.) In 1842, Lovelace was tasked with translating an article from French into English for Charles Babbage, the “Grandfather of the Computer.” Babbage’s piece was about his Analytical Engine, a revolutionary new automatic calculating machine.

Ada Lovelace was an English mathematician who lived in the first half of the 19th century.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)